About Dravet Syndrome

- Dravet Syndrome is a rare and lifelong form of epilepsy.

- It affects around 1 in 16,000 people.

- The syndrome is named after Dr Charlotte Dravet, a French doctor who first identified a group of children that had this type of epilepsy.

What causes Dravet Syndrome?

- In around 80% of patients (4 out of 5), Dravet Syndrome is caused by a change in the gene known as SCN1A.

- This gene tells the body to produce a protein that helps make and send signals in the brain.

- Changes in other genes, such as PCDH19, GABRA1, SCN1B and SCN2A, have also been found in people with a diagnosis of Dravet Syndrome.

Dravet Syndrome and seizures

- Most children with Dravet Syndrome start having seizures between the ages of 4 and 8 months.

- The first seizure may be triggered by a fever (high body temperature), a vaccine-related fever, or a hot bath.

- Children with seizures in the first year of life often have jerking movements either down one side of the body or on both sides. The side involved often changes. The seizures often last for a long time and occur in clusters. Immediate medication may be needed to stop them. This may be given either as drops inside the cheek (buccal), as an injection via muscle (intramuscular), or via the veins (intravenous).

- These types of seizures, along with single jerks known as myoclonic seizures, point to a diagnosis of Dravet Syndrome.

- Early diagnosis is important so children can receive the most appropriate medication.

- After the age of 1 year, common triggers include fever, an illness, a hot bath, or flashing lights.

- Children may experience different types of seizures (focal and/or staring episodes).

- Episodes of ‘status epilepticus’ (long-lasting seizures) are common.

- Seizures may occur often and may be reduced with medication.

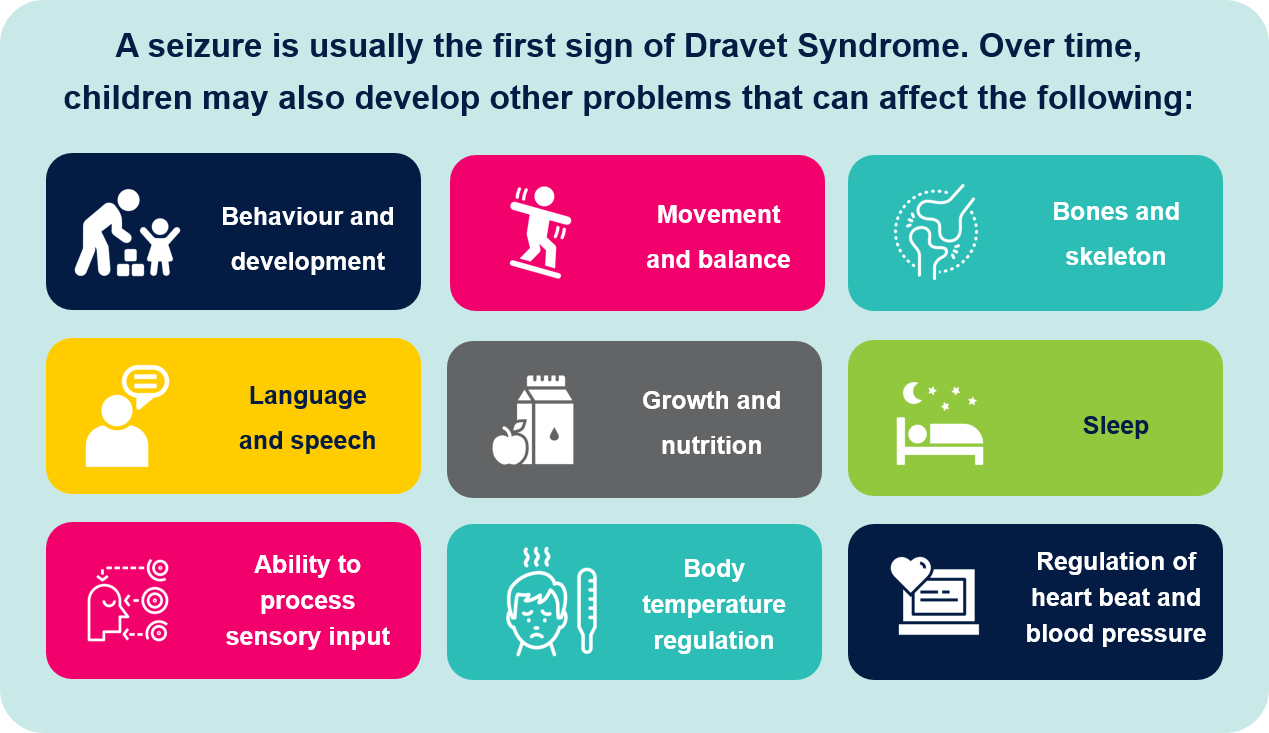

How does Dravet Syndrome affect a person over time?

- Dravet Syndrome is variable in every child.

- How the condition changes over time is different in each child too. This makes it difficult to accurately predict the future.

- Studies that have followed people with Dravet Syndrome from childhood to adulthood (called natural history studies) have provided some general insights into the changes that may happen as children grow up.

- From these, we know that seizures usually continue into adulthood, although the types of seizures may change.

- Other problems usually continue through childhood, worsen and then become stable.

- The table below gives more details about the problems and the changes that may be experienced into adulthood:

Seizures

- Certain types decrease (myoclonic, focal, staring episodes)

- Less status epilepticus, especially after 30 years of age

- Convulsive seizures usually only happen when sleeping at night

- Temperature sensitive seizures usually decrease

Movement disorders

- May worsen with age

- Individuals may have trouble walking, and have a “crouch" style of walking (gait) or uncoordinated movements (ataxia)

- May develop symptoms of Parkinson disease, with limited movement, rigidity (altered tone), gait with small steps and/or falls

Behavioural issues

- Often continue

Sleep difficulties

- Often continue, and individuals may have problems falling asleep and staying asleep

What is the life expectancy of a child with Dravet Syndrome?

It is difficult to predict life expectancy or provide accurate insights into the future of individual patients with Dravet Syndrome, as the long-term impact of treatments introduced in recent years (and those being developed at the moment) is not yet known.

Overall, the lifespan of people with Dravet Syndrome is generally shorter than that of people without Dravet Syndrome, but there have not been enough studies yet to completely answer this question. There are many reasons why little is known about older people with Dravet Syndrome:

- Most studies focus only on children or young adults, and there are still only a few studies that include adults.

- Some patients with Dravet Syndrome are lost to follow-up.

- Older individuals may not have had an accurate Dravet Syndrome diagnosis.

It is estimated that 10–20% of children with Dravet Syndrome die before 10 years of age. People with Dravet Syndrome are at an increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Overall the limited information available suggests that SUDEP is the main cause of early death in adults with Dravet Syndrome. More information about SUDEP and what to do if you are concerned can be found here.

Treatment advances and future research

There is a lot of research into Dravet Syndrome happening around the world, including research aimed at:

- Developing treatment that is more effective at controlling seizures, as well as improving other difficulties such as movement and behaviour

- Gaining a better understanding of how Dravet Syndrome affects adults

- Working out how to best manage symptoms.

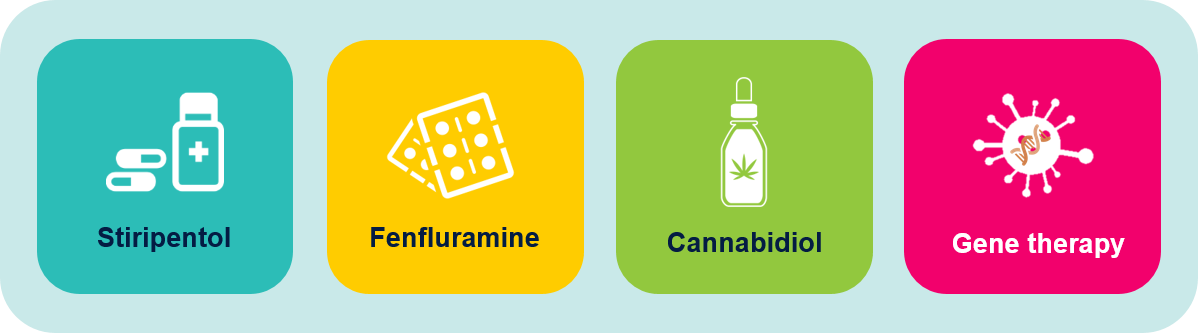

New effective treatments that are now available or in development are shown below. It is hoped these treatments will change the way the future looks for children and adults with Dravet Syndrome:

Research on Dravet Syndrome

Patient support groups often have the most up-to-date information about Dravet Syndrome, including current research and information about clinical trials that your child may be able to join. The Dravet Syndrome Foundation website is a good place to start. This organisation has a well-respected scientific advisory board that ensures the information is accurate and up-to-date. Pages on this website that you might find helpful include:

- Dravet Syndrome in Adults

- Research: The Dravet Syndrome Foundation is actively involved in research to develop better treatments for individuals of all ages.

You could also discuss recent research and your child’s future with your child’s neurologist, as your child moves on to adult care.

- To find out more about current clinical trials, you can register with the Australian Clinical Trials Network, as shown on this website.

- There have been very encouraging recent trials with cannabidiol (derived from cannabis), stiripentol, and fenfluramine. Early human gene therapy trials have also started. There is some evidence that the ketogenic diet and vagus nerve stimulation may be effective in people with Dravet Syndrome.

- The Genetic Epilepsy Team Australia website is a source of local information and support for families with children who have genetic epilepsy.

- Facebook groups can be a useful source of support. However, it is important to realise that every child is different, and your child’s future may be very different to other children in the group.

------------

Content on this page was generated via the GeneCompass project. The following article provides more information about the project:

- Robertson EG, Kelada L, Best S, Goranitis, I, Grainger N, Le Marne F, Pierce K, Nevin, SM, Macintosh R, Beavis E, Sachdev R, Bye A, Palmer EE. (2022). Acceptability and feasibility of an online information linker service for caregivers who have a child with genetic epilepsy: a mixed-method pilot study protocol. BMJ Open, 12:e063249. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063249