The following steps illustrate how clinical trials typically work.

Step 1: Eligibility criteria:

Only some people who want to join a clinical trial will be able to. To participate in a specific clinical trial, your child will need to meet the eligibility criteria.

- Criteria that must be met to allow someone to take part in a clinical trial are called the ‘inclusion criteria’.

- Criteria that prevent someone from taking part in a clinical trial are called ‘exclusion criteria’.

- The criteria may be based on many things, including:

- Age

- Gender (male or female)

- The type and stage of a disease or condition

- Previous treatment history and other medical conditions.

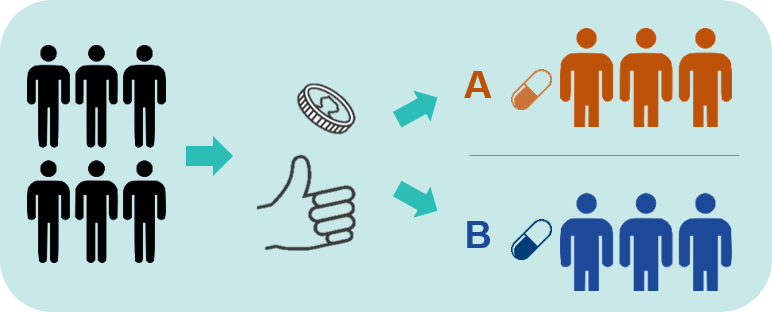

Step 2: Randomisation:

- Some Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials involve randomisation.

- This means that some people are allocated to Treatment A (the new treatment), and some people are allocated to a different treatment (called the control).

- The process of randomisation is like flipping a coin (see image above).

- The people in the control group may be given:

- Another treatment that is already being used to treat the health condition, or

- A placebo. This is a pretend treatment that is made to look like the real treatment. An example of a placebo is a sugar pill or sugar liquid. A placebo is not expected to improve a person’s health condition.

What this means is...

In some clinical trials, many people are not given the trial treatment.

- Sometimes, a new treatment is given by itself, with no comparison treatment. In this case, the effect of the treatment is compared with what we know about the 'natural history' of the condition.

- The 'natural history' is how a condition usually affects people when they are not given treatment. We know this from looking at data from natural history studies.

- A natural history study for all children and adults with the combination of seizures and impacts on learning or development (the genetic or suspected genetic epilepsies) will be starting across Australia soon.

Step 3: The Clinical Trial

- All clinical studies in Australia are very closely regulated and monitored. They must be approved by special committees within hospitals and government organisations called ethics committees. These committees make sure clinical trials are carried out in an ethical way, in keeping with national and international laws.

- Clinical trials vary in how long they last. They may last weeks, months or sometimes years. This will always be stated in a clinical trial’s information sheet.

- People in clinical trials may need to make regular visits to the clinical trial centre for treatments and check-ups.

- It is possible to ‘opt out’ of a clinical trial at any point. Your decision to withdraw will not affect the relationship between you, your doctor or the hospital. If you decide to withdraw, your child will be offered the best-known therapies.

Step 4: After the trial finishes

- When the clinical trial has finished, researchers work out or ‘analyse’ how well the treatment worked and examine its side effects.

- They will share the trial results with others through meetings and the published literature, and often through patient organisations.

- If the results show that the treatment worked, the treatment may be used in other people with the same health condition.

- Sometimes more clinical trials may need to be done.

What this means is...

Many clinical trials do not lead to a new treatment being available.

------------

Content on this page was generated via the GenE Compass project. The following article provides more information about the project:

- Robertson EG, Kelada L, Best S, Goranitis, I, Grainger N, Le Marne F, Pierce K, Nevin, SM, Macintosh R, Beavis E, Sachdev R, Bye A, Palmer EE. (2022). Acceptability and feasibility of an online information linker service for caregivers who have a child with genetic epilepsy: a mixed-method pilot study protocol. BMJ Open, 12:e063249. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063249